Post

A Marshall Plan for rural America: School Supported Agriculture

Is current political discourse devoid of new ideas? While the political architects in The White House peddle a mean-spirited deconstructivist agenda, “the resistance” is rediscovering old roles for government in our lives. It’s as if central casting for the endless blockbuster reviews and revivals, like Beautiful or Hello Dolly, has staged today’s current drama: A know-Nothing populist revival on the right and a revived New Deal on the Left (but this time, Green).

While the New Green Deal’s sprouts are only beginning to push through the dirt with specific shoots (as discussed in this Civil Eats story), I recognize the power in referencing a bygone era in politics that took seriously critical questions about the obligations we have to one another (as mediated by our government).

I give the New Green Deal credit for planting itself on strategic ground to craft a national agenda. If this can work for the New Deal, what about the Marshall Plan? Can it be updated to provide a useful framework for these times?

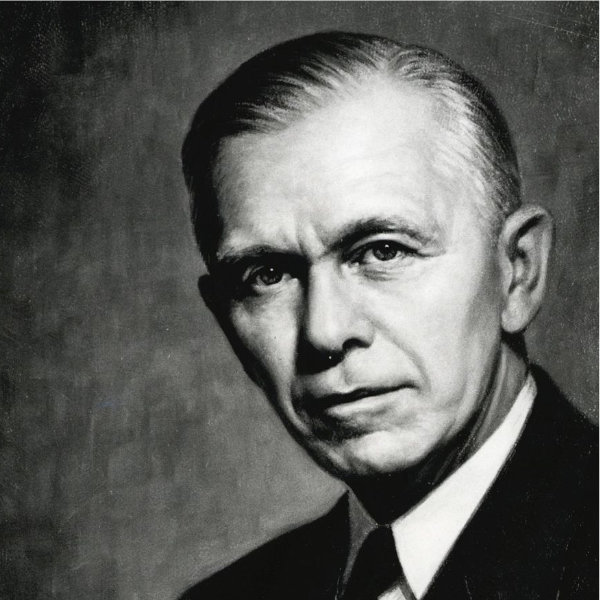

Named for its chief proponent, US Secretary of State George C. Marshall, it is the $12 billion aid program (circa 1948 value) given to European nations to restart and develop their economies after World War II. Its official name — The European Recovery Program — speaks to its five-point goals: “to rebuild economies, remove trade barriers, modernize industry, improve European prosperity, and prevent the spread of Communism.”

Debate continues to this day about the Plan’s efficacy: For instance, was it big enough to have impact or did it reach Europe soon enough to be THE catalyst for growth? Was it good for the receiver or the giver? These questions aside, there is little question about its popularity in the annals of American foreign policy or its ability to demonstrate the creative power of government. These speak to the challenges of this current era: Consensus is difficult to find anywhere in America – consensus that traverses geography and political ideology.

Electoral results and a myriad of polls continue to keep members of the political class scratching their heads: Ours is a divided nation. It is divided in its dreams and hopes; and divided in how it experiences the economy, public resources, and the civic infrastructure that makes up everyday life. For instance, was Obama’s incremental effort to deliver healthcare as a universal right the last gasp of a people able to rally around big ideas FOR something? Fear of the outside world manages to mobilize many AGAINST something, but that’s an entirely different impulse.

One intriguing and unexpected wrinkle in an otherwise bleak picture of Americans driven narrow by self-interest and to bond only with those who are like themselves is this: The vision for a future articulated by and experienced through food. Whereas the industrial food system isolates us and hides its true costs, the food movement provides a platform to reestablish connections: Urban with rural, traditional knowledge with science, and supply with demand. Where advocates and eaters together forge new and regional webs of commerce and community, there is hope. In short, this is the start for a new social contract.

This is why School Supported Agriculture may provide a logical next step to elevate the farm-to-school agenda of school gardens, kitchen curricula, and the myriad of enterprising efforts to deliver healthy food and tactile learning for kids whilst enabling rural economies and dignity to flourish.

Visionary restaurateur, author and activist Alice Waters (seen here discussing school lunch with US Senator Michael Bennet) coined the name, School Supported Agriculture. It is based upon the nimble, DIY network fo Community Supported Agriculture (or CSA) relationships between eaters and farmers. The genius of CSAs is the concept that consumers share in the risk of agriculture through investment. Each consumer purchases a season’s crops on the front-end (when the farmers need the cash) and receive weekly boxes of what comes in (with volume determined by the practical realities of weather and skill). Waters contends that CSA members and restaurants, like her Chez Panisse, learn to understand and love rural communities because they forge ties through investment.

What if we were to do more than nibble around the edges of the campus garden and cafeteria? Waters calls for big, bold thinking: Use the public purse of school systems to reimagine school lunch as an academic subject. Equip school kitchens to become centers of learning. Procure delicious food directly from local farmers so as to bring farmers into the classroom. To borrow the imaginative scope of the original 1948 Marshall Plan for post-War Europe, I propose a School Supported Agriculture. Invest in children (our collective future) as if they matter; and cultivate an agriculture that generates a future. In other words, I propose a Marshall Plan for Rural America that builds upon the amazing work already underway: The Center for Good Food Purchasing and Food Corps are two examples of efforts that recognize the complexity of unwinding the opaque system that shapes national diets.

Whereas the original Marshall Plan sought to rebuild economies, remove trade barriers, modernize industry, improve European prosperity, and prevent the spread of Communism, I propose to:

- Rebuild rural economies: The industrial food system extracts wealth from rural communities. We propose using the public purse of the public schools mitigate the risks moving from an extractive model to a regenerative one. The School System feeds 29.4 million children each day. And yet, this system procures Fast Food. What if schools forged direct relationships with the nearby small farmers who raise regenerative organic food for our nation’s children?

- Remove trade barriers: The industrial procurement system -- with its centralizing tendencies, rules and regulations – prevents small farmers from accessing a market hell-bent on speed, efficiency and price (as opposed to quality, freshness and nutrition). The procurement system must be redesigned to open up new markets.

- Modernize industry: Agriculture and the trade routes that get products to market are designed for a global, get big-or get out model for doing business. Let’s modernize family farms, cooperatives, and distribution mechanisms that value children.

- Improve prosperity: Rural and urban communities both deserve to do better. Let’s use the power of the public purse to feed children real food and farmers to generate the kind of wealth that remains circulating in rural communities so they can flourish.

- Prevent the spread of populism: The unfettered growth of big cities at the cost of rural communities and small towns creates the conditions where prosperity is enjoyed narrowly and animosity grows between urban and rural, and social isolation allows for desperation and intolerance to fester. The growth of populism undermines civil life in America. In order to support the oxygen for democracy, we must provide economic opportunity, dignity and political support to marginalized rural communities who grow the food that feeds the children who are our future.

Policy experts continue to point to the complexities of reforming the deeply entrenched school food system. However, if instead of taking each heroic swipe against the system separately, maybe it is time to rally around big and imaginative ideas. After all, while Alice Waters may simply run a small restaurant in one city, her ideas about rethinking the dinner plate have transformed the way we think about eating out. Let’s turn our attention to how and why and what kids eat in at school. We have a future to win.